In his autobiography Chronicles, Bob Dylan discusses how starting in the mid 60s, audacious new artists like the Rolling Stones and the Who "breathed new life and excitement" into the doldrums of what before them had been the bland monotony of early 60s radio pop music in the era of pre-Beatles pap. Except for a few gems like Motown hits and Franki Valli, it was a wasteland back then. Reminds me of what the comics scene was like, post-Code, before the thrilling advent of Kirby, Ditko and writer Lee's then wildly innovative and extra-dimensional concept of fleshing out his characterizations via "heroes with problems." Even today, the excitement and ragged vitality of those 60s Marvels is self-evident and pops and crackles off the pages.

How countercultural mindsets got slipped into the coffee of staid mainstream comics

The new wave of baby boomer comic creators who entered the field in the late 60s and early 70s such as Dennis O'Neil, Jim Starlin, Steve Gerber and Steve Englehart in many cases protested the Vietnam War, toked reefer and such and were as counterculturally liberal as the best of them, but their heart belonged to superheroes and science fiction, not the socio-political and sexual outrageousness of the undergrounds (a middle finger to Dr. Wertham and the Comics Code if ever there was one). Their work on Dr. Strange, Howard the Duck and Warlock was surreptitiously hip and risque, not overtly. The more obviously preachy work of O'Neil and Adams on Green Lantern/Green Arrow has probably aged the worst despite its noble intentions and excellent execution, due to its direct engagement of socially "relevant" themes in the medium of superheroes which perhaps is not the most conducive forum for that effort. A nice compromise between the adult sophistication, cuss words and t & a of the undergrounds and the exciting science fiction and fantasy pulp elements of the mainstream was reached in the pioneering 70s "groundlevel" comic series Star * Reach. This comic-sized anthology was sold at the time only through mail order, head shops and a sprinkling of early comics shops, with zero Comics Code jurisdiction, no ad distractions and creator-owned material. It was a real trailblazer publication which built on the legacy of Witzend and paved the way for the racy and avant garde adult fantasy magazines of the late 70s like Metal Hurlant and Heavy Metal, which prompted Epic.

Captain Marvel #28 (September 1973) - Jim Starlin

Pioneering sf anthology "groundlevel" series Star * Reach #1 (1974), variant cover by Jim Starlin. (The other cover was by Howard Chaykin).

The dope smoking anarchists and artistic subversives of the underground like Crumb, Victor Moscoso and S. Clay Wilson clearly had a big impact on these aforementioned mainstream creators of the 70s. Jim Starlin, fresh out of Vietnam, would take the Captain Marvel strip, and Warlock, into realms of psychedelic and mind-melting transformation, bemused self-awareness and religious allegory, which went far beyond the initial conception of these characters under the very able but decidely unhip hands of the more senior bullpen staples Lee, Kirby and Kane.

Dr. Wertham and the forces of reaction = anal retention. The undergrounds and their aftermath = anal expulsion. Proper regularity not established until more nutritious fusions of adult stories and exotic art came along with Metal Hurlant, Fantagraphics, Spiegleman's RAW et al.

Dr. Wertham and the forces of reaction = anal retention. The undergrounds and their aftermath = anal expulsion. Proper regularity not established until more nutritious fusions of adult stories and exotic art came along with Metal Hurlant, Fantagraphics, Spiegleman's RAW et al.

The hysterical and reactionary forces represented by Dr. Wertham, the Kefauver subcommitee, and the Comics Code Authority definitely retarded the development of a medium that creators like the E.C. artists, particularly Bernard Krigstein, were on the verge of transforming into a more mature and sophisticated means of graphic storytelling. To me, a recent work like "The Courtyard"/"Neonomicon" written by Alan Moore picks up where

E.C. left off, absorbing the freedoms afforded by the subversiveness of the undergrounds with a serious literary intent and brilliant execution in concept, dialogue and art. Another point worth noting is that in later decades, the deservedly reviled Dr. Wertham unexpectedly became a more admirable advocate for the healthy virtues of comics fandom, see his book "The World of Fanzines" (1974) and the related revealing essay by comic critic Dwight R. Decker, who met and interviewed him for the piece. See Art-bin.com/art/awertham.html

Huh? The worst comic book of all time...by Neal Adams??

According to the "World's Worst Comics Awards No. 2" (1991, Kitchen Sink), this is the single worst comic produced in the 25 year period prior to its release. This abomination of a book combines a concept which is preposterously juvenile even by comic book standards, overblown bathos in place of characterization, racial pandering, unimaginably godawful prose (or as the Kitchen Sink publication called it, "the most self-indulgent, angst-ridden, second person narration ever to stain paper") and the dopiest dialogue right from jump street on page one: "Hands off, jerkhole! The party's over! We're forming a union! My foot and your face!" It goes without saying that the artwork is excellently executed, but we'd expect a brain surgeon to be steady with his hands, or a top-notch studio musician to play the notes correctly, so no credit there. Plus the stilted hokiness of the Adams style is accentuated by this train wreck of a story, the product of a gifted draftsman totally lacking in a self-aware sense of his own ridiculousness. When paired with a top-notch genre writer like Denny O'Neil or Roy Thomas, Adams produced some of the most thrilling adventure and superhero comics ever done. Left to his own devices, by 1983 he had degenerated to pure dogshit. An absolute must for any collection, to mark its nadir.

|

Jim Steranko: a legend in more than his own mind? Self-cultivated mysterioso or egomaniacal blowhard??

The good ole Ukrainian Pennsylvanian mysterioso who had multiple brothers die on the railroads and was raised dirt poor by dismissive parents and scrapped metal in the streets to buy magic and art supplies while an uncle brought him boxes of comics and newspaper strips to fire his imagination and steel his resolve for his first love: comics, self-made man of mystery and escape magician, early rock and roller who claims he invented the go go girls in mini-skirts concept, hardened street fighter who warded off much bigger bullies, basis for the Escapist character in author Michael Chabon's Pulitzer Prize-winning tale of Jewish survival, "The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay," the pop art provocateur and member of the Witchdoctor's Club in NYC with Orson Welles and Isaac Asimov...gentleman Jim Steranko. Rabble rouser, dodger of deadlines and defier of page conventions under Stan Lee. Ace historian who recounted the tales of the early, wing-it-as-they-go days at the dawn of comic book creation in the late 30s and early 40s with the earliest pioneers flourishing then such as Will Eisner, Lou Fine, Siegel and Schuster, Jack Cole, Mac Raboy, Gardner Fox, Charles Biro et al. These tales were related to Steranko by Kirby at the Kirby home in Long Island in which Jack pumped out his greatest works in collaboration in the 60s with Lee who was in NYC in or near the Marvel offices. Down in that basement, Jack was hunched over his drawing board working non-stop for he vowed his kids would never suffer the lack of middle class comforts that he had to endure through the Great Depression in the Jewish tenement districts of New York, so he toiled in his basement non-stop like a whirling dervish of ingenius productivity out of which sprang the Marvel universe, while his doting and practical wife Roz, who was a managerial whiz who juggled all the household responsibilities about which Jack was a space cadet, this doll and firecracker of a lady fed pastrami sandwiches and pickles to Jim and youngsters like Marv Wolfman and Len Wein, who were always welcome as teens to drop by. These lively, perambulating, and exhaustively detailed discussions between Jack and Jim, before which Steranko would perform magic tricks for his and Roz's kids, formed the basis for the monumentally thorough and exhaustively encyclopedic giant-sized stunning two volume set, "The Steranko History of Comics."

Keep in mind that Steranko is of the astrological sign of Scorpio, so there's more than a touch of self-mythologizing mystique-making at play here.

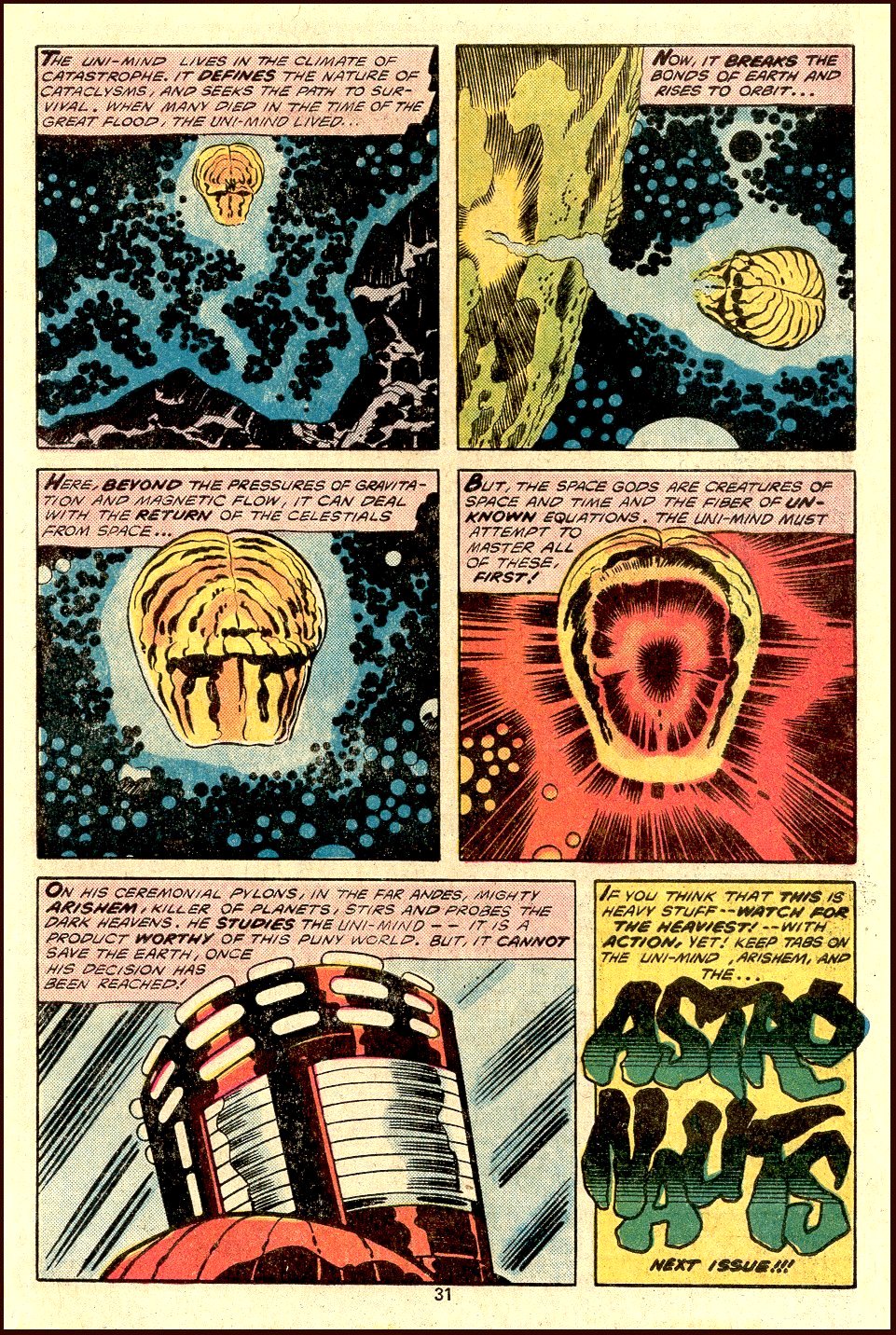

The single finest and most mind-bogglingly imaginative Kirby issue I've ever seen? Eternals #12, "Uni-Mind" (1977)

A shimmering, mindboggling apotheosis of transcendence from a quirky non-psychedelic talent in fullest flower, from that visionary from Brooklyn, as Alan Moore called him.

The Silver Surfer - from stoic skyrider to "galactic crybaby."

Editor and writer Lee wisely made Kirby step aside for the Surfer's solo title, since Jack's vision of the character was a cold, stoic cosmic herald and sentinel, whereas Buscema infused the character with the noble bombast, altruistic soul, and social conscience more suitable for the direction in which Lee wanted to take the character.

The definitive Batman, or damn close...

This two-parter is the smoothest transition I'm aware of from one writer to another on a major mainstream title, as Steve Englehart ended his superlative run on the previous issue and Len Wein took over for both of these issues, each with artist Marshall Rogers. It's also one of the peaks of the entire Batman oeuvre, and was genuinely psychologically chilling in its depiction of Clayface's doomed effort to escape his "hyperpituitarism which hideously distorted (his) body" and the villain's haunting love for his wax figure lover Helena. The creative team also dug deeply into the guilt and rage which drove Batman's monomania, an obsession with thwarted his future with the woman who was perhaps his truest love, Silver St. Cloud. Plus the rich and supple inking jobs by Dick Giordano are among the best I've seen. (Terry Austin inked the cover on the first one).

Saying goodbye too soon to some superlative contributors to comic book history...

Bernie Wrightson (1948 - 2017)

Early fanzine art by Wrightson, who was a prolific contributor to Squa-Tront, Spa Fon and so forth.

"The Pepper Lake Monster" - Creepy #113, November 1979, story and art by Wrightson. This story was a triumphant return to the comics form for the artist, after many years where he was mainly preoccupied in the more lucrative and respectable field of fantasy art lithographs (see The Studio, Dragons Dream 1979 for the astounding illustrated chronicle of his late 70s studio arts collaborative co-op in New York City with peers and pals Jeffrey, later Jeffrey Catherine Jones, Michael William Kaluta and Barry Windsor-Smith). He was head and shoulders over most of his peers at Warren, save maybe Richard Corben as a dynamic action storyteller and Esteban Maroto as an exquisite renderer.

Wrightson, Jones, Kaluta and Windsor-Smith - "The Studio"

Rock stars!

Remembering the Studio - via YouTube