1) The works of Alan Moore with artistic collaborators, especially Swamp Thing, Watchmen, Promethea and Neonomicon

"The old guard knew immediately that despite Moore's often shambolic plotting, they were seriously outclassed by this hairy anarcho-freakazoid dope-smoking Brit from Northhampton. Moore was superior not just as a writer, but also as a thinker and reader. Quite simply, he had a deeper reservoir of vast background knowledge from which to draw. It seems that the more one learns about science, history, psychology, political theory, metaphysics and philosophy, and many other interdisciplinary understandings, the more one realizes the radiant layers of meaning Moore has somehow crammed and compacted into his works with such offhanded yet self-consciously deliberative brilliance."

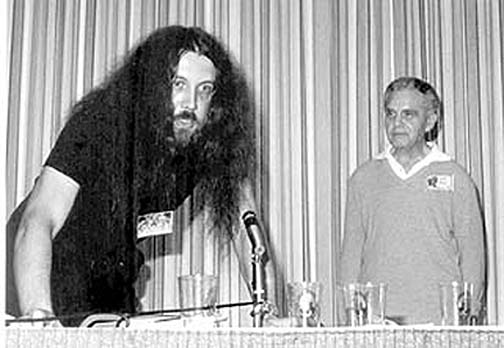

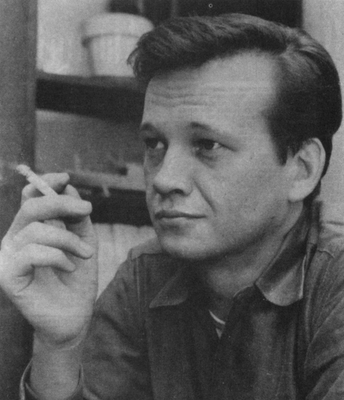

Passing the torch: Moore at a 1980s convention with with "Brooklyn visionary" and fellow comic book giant Jack Kirby (1917 - 1994)

Yes, I concede that he can be an

unbearable prima donna and bridge-burner who needlessly destroys

relationships with old friends and collaborators, he does in fact

consistently depict (although he hardly endorses) extensive rape scenes as

pointed out much to his chagrin by his upstart rival, postmodernist pop

provocateur and lesser talent Grant Morrison, and his highly studied

snake-fingered mysterioso occult magus and man of integrity middle-finger to

the corporate man schtick can get old. The record shows he's often

volitionally entered into contracts where he has no ownership and then bites

the hand that feeds him as often as he valiantly fights for creative

autonomy, control, and freedom. Furthermore, Moore throughout his career has

appropriated from other pop cultural sources and tropes and material with a

promiscuous abandon and self-conscious meta-fictional game playing more

suited to a kaleidoscopically synthetic talent rather than

to the searchingly original, multi-leveled signifier and chronicler of the

human spirit embedded in complex systems that he's capable of at his best.

However, despite these excesses

and limitations, bonafide genius Alan Moore has done for comics what Joyce

did for the novel, Picasso for the visual arts and Dylan for the popular song

in the 20th century: opened up his respective art-form as none before or

after him, to the limitless complexity of human experience and conflicted

socio-cultural reality-perspectives, mixed with constant experimentation with

narratives, forms, genres, points of view, and daring deconstructions and

reconstructions of landscapes of the imagination, societal archetypes and the

re-making of myths. His preoccupying themes have focused on searing

depictions of anarchy's back and forth with its evil twin fascism,

psycho-sexually tinged depth psychology as the backdrop for super-heroic

posturings, the shadow of the Cold War's threat of looming holocaust, views

which are often mischaracterized and misunderstood regarding his stances on

gender, race, sexual orientation and human dignity (views which ultimately

tilt toward more enlightenment), the intertwining of sexual repression and

wild expression with the outbreak of the First World War and its aftermath, a

repudiation of the so-called grim and gritty depictions of nihilism he helped

spawn (rather than random rampaging disorder, Tom Strong and Promethea

embraced a hopeful re-infusion of optimism and a sense of benign design in

the cosmic order of things), and his own deeply idiosyncratic poetic

pontifications and ruminations of his views of space-time's circularity and

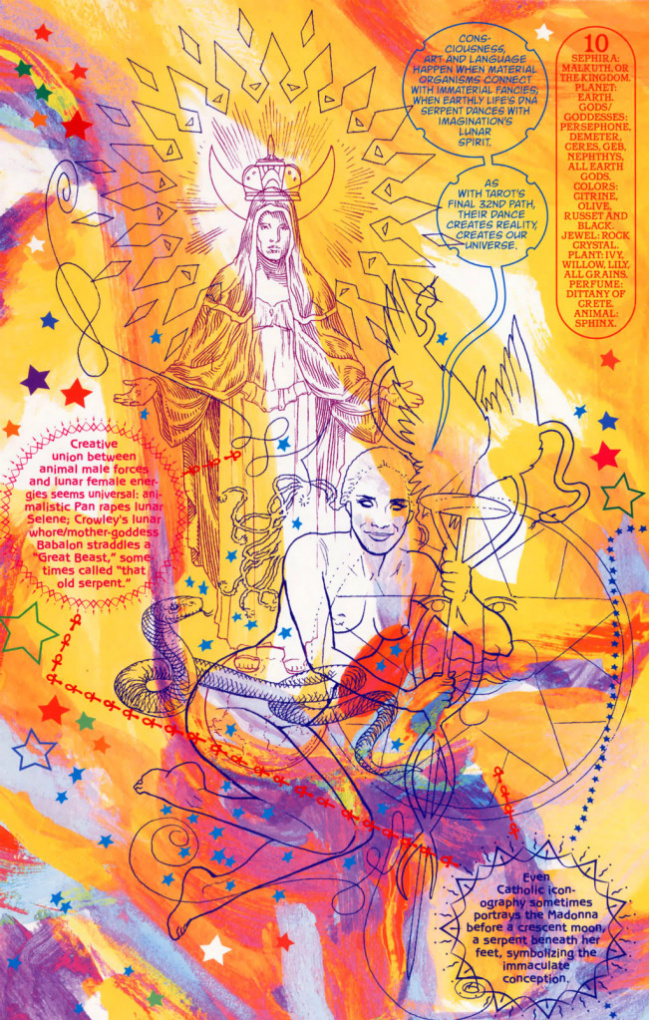

Tantric/Cabalistic sex-magick and mystery rites. Pretty advanced stuff for

funny books.

Swamp Thing #34 (March 1985), "Rite of Spring" - Alan Moore, Stephen Bissette & John Totleben

Moore is generally and rightfully considered the finest writer in comic book and graphic novel history, in no small measure due to his uncanny ear for realistic dialogue, the piercing lyricism and ironic bite of his prose, and the structured layers of interconnected density worthy of one of his literary mentors, Thomas Pynchon. Moore though has stated that he's no great shakes; in the world of proper novels and literature, we expect such qualities from a Steinbeck or a Faulkner as a matter of course. Only relative to the genre hacks of the freelance mill of the comic book schlock houses is he so great, goes this theory. Well, I say that Moore at his finest, when he mixes harmoniously with his artistic counterparts (and don't forget that he's a control-monger as a scriptwriter worthy of Kurtzman, constantly directing his artists' work on the page and so in that sense he too is a contributing artist), does things only possible in graphic narrative -- see "Rite of Spring," "Pictopia," and the didactic spiritual polemic Promethea #32. And he does so with more depth, humanism and shimmering vision than ever seen before by any of the previous creators whose shoulders he's stood upon, save perhaps George Herriman or Windsor McCay (whose abstract and dreamy comic strip reveries were of a different order, since they aspired to visual splendor and poetic whimsy, not novel-like complexity, richness of character profiles, narrative inter-threading and social engagement). Even when he's spoofing on or stooping to the level of the hacks, as with his Supreme material from Image in the 1990s, he's almost always fun as hell, endlessly interesting (as noted by pop culture critic Douglas Wolk), often hilarious and with a satirical versatile intelligence and world-spanning insight that leaves three or four trick pony, bitter misanthropist and reluctant bourgeois darling R. Crumb in the shade. |

When Jimi Hendrix first hit the rock and roll guitar scene in swinging London circa 1966, Eric Clapton convened a clandestine meeting with Pete Townsend in a darkened movie theater and let Townsend know that there was a new kid in town from Washington state who would blow them all away. Similarly, when Moore hit the American comic book scene in 1983 when he and Steve Bissette were recruited by co-creator and editor Len Wein to revamp the dessicated, played-out and failing horror title Swamp Thing, Moore's peers started shitting bricks. Guys like his own editor Wein, Dennis O'Neil, Marv Wolfman, Doug Moench, Roy Thomas, et al. were capable and proven genre craftsmen and among the so-called hacks of comic book writing who paid their dues in the thankless crucible of over a decade of hitting their deadlines to push paper product for their check-signers. (But do these decent and hard-working men really deserve bashing when when they could have been pipe fitters or insurance adjusters or something similarly nondescript but instead they chose to be freelance storybook pamphlet entertainers whose worst sin was to deliver solid, and sometimes not so hot, kids' diversionary fantasies, which in the broader context of the arts were pretty much at the level of a Louis L'Amour western novel or a good Twilight Zone or Star Trek episode?) The old guard knew immediately that despite Moore's often shambolic plotting, they were seriously outclassed by this hairy anarcho-freakazoid dope-smoking Brit from Northhampton. Moore was superior not just as a writer, but also as a thinker and reader. Quite simply, he had a deeper reservoir of vast background knowledge from which to draw. It seems that the more one learns about science, history, psychology, political theory, metaphysics and philosophy, and many other interdisciplinary understandings, the more one realizes the radiant layers of meaning Moore has somehow crammed and compacted into his works with such offhanded yet self-consciously deliberative brilliance. His storytelling prowess and the range of his keen cultural and multivariate literacy, both deep and vast, continues to amaze us simpler mortals. The grand, protean, riddle-laden and sometimes spastic outpourings of his unique set of gifts are the finest his beloved medium has seen.

|  |

|

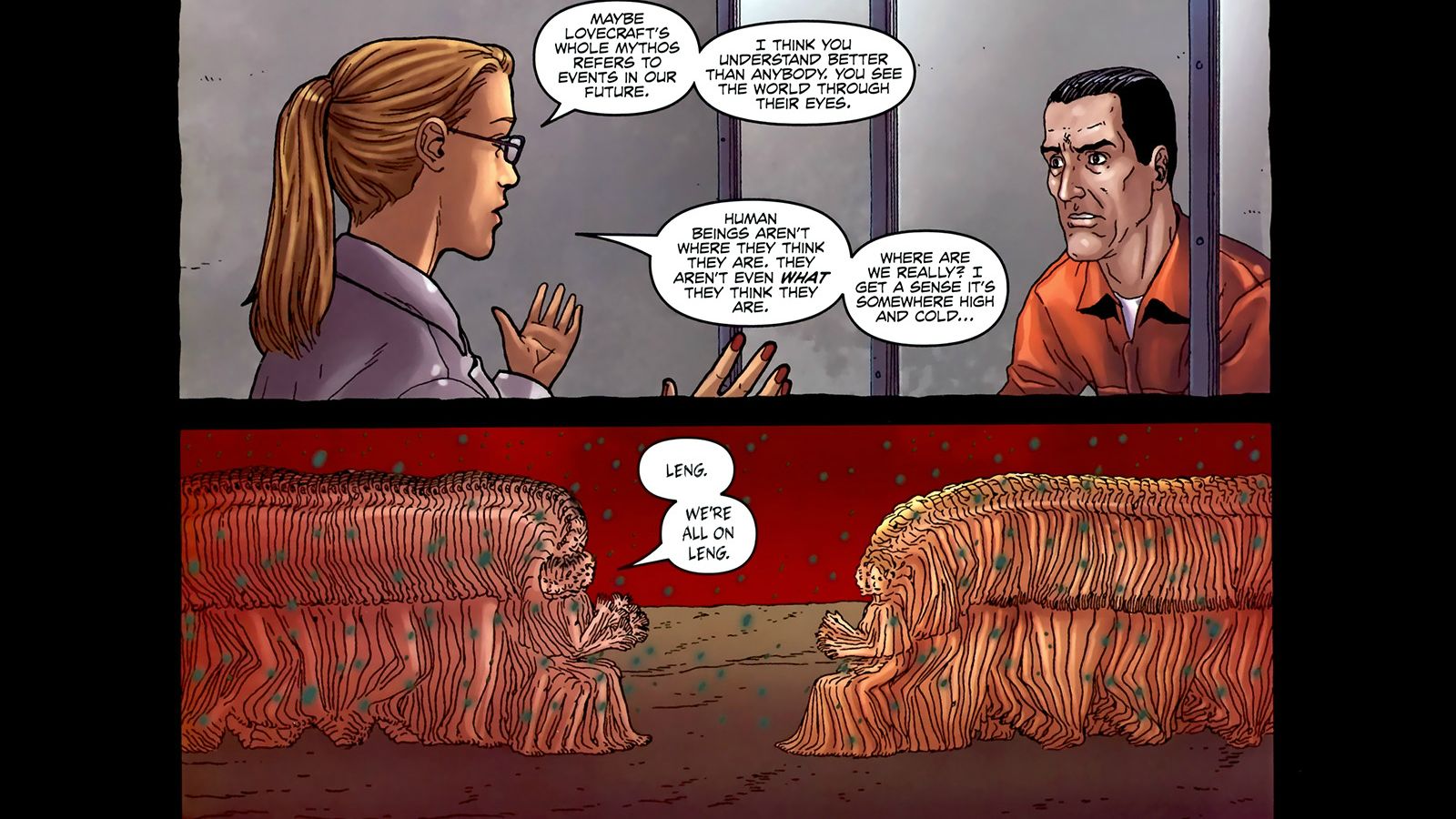

| Done with Jacen Burrows, Neonomicon (2010 to 2011) is perhaps the most technically excellent and well-executed example of the comic book story I've witnessed in about forty years of collecting. Bloodcurdling psychological horror, a maze with no escape, full of creeping haunting metaphors and nobody's idea of a kiddie book. And Burrows' understanding of the subtleties of body language and the nuances of human expression and interaction compares well to the work of our finest recent filmmakers, as we witness a new master of a medium that's separate, equal and genuinely different in the places it can take us in a way that cinema could never dream. |

(1924 -1993)

3) Love and Rockets stories by Jaime Hernandez

Los Bros. Hernandez: Gilbert, Jaime and Mario. Center: Jaime Hernandez (1959 to present)

4) Fantastic Four by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

The quintessential writer/artist team Stan and Jack, in happier times (mid-60s).

Fantastic Four #45 (December 1965) - The debut of the Inhumans

The quintessential writer/artist team Stan and Jack, in happier times (mid-60s).

"The ragged charm and ebullient energy of these comics remains, and makes them the most vital superhero books ever done -- and the ones which are the most sheer, good clean fun."

Fantastic Four #45 (December 1965) - The debut of the Inhumans

Over half a century later and the pages still crackle with snappy dialogue and hyped-up irresistible prose, eye-popping in-your-face action storytelling, and constantly exploding, morphing, surprising innovation. For a brief spell it was Camelot and then the mid-60s era of rejuvenating optimism and audacious daring (matched in pop music by the Beatles and Motown); imagine the impact on the budding imaginations of young readers including Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman and even higher-brow-than-thou Gary G. Groth when this cascading succession of characters and concepts hit the newsstands. The earth/water/fire/air-derived main cast, Dr. Doom, the Inhumans, Black Panther, the earliest seeds of the Skrull-Kree War and Adam Warlock, the Silver Surfer and Galactus and the Negative Zone -- Stan and Jack sure were on a roll. The earliest superhero characterizations from the late 1930s on were little better than cardboard and based almost solely on the cheesy concept itself, i.e. Ray-Man, a big tough guy who shoots rays out of his hands to fight crime, big frigging deal and how one-dimensional. Gardner Fox over at National (later known as DC) on the Justice League of America and Adam Strange had made progress with his intricate plots, budding social conscience and scientifically sound scripts, but Stan Lee went a step further when he introduced the 2-d "heroes with problems" conceit (radical for its time even if quaint today). In tandem with Kirby's frenetic storyboard momentum, this creative team made the dysfunctional dynamics and galaxy and Sub-atomica-spanning super-heroics of their pages come alive. Alan Moore's later ventures into 3-d characterizations (closer to human complexity and with people more deeply damaged and a closer simulacrum to the verisimilitude of real life) would have been impossible without this stepping stone and lightning rod of inspiration. Sure Marvel and Disney have mined this early 60s creative phase of prime Lee-Kirby-Ditko to the tune of billions and not yet made it work on the big screen in the case of the FF, but the ragged charm and ebullient energy of these comics remains, and makes them the most vital superhero books ever done -- and the ones which are the most sheer, good clean fun.

Fantastic Four #50 (May 1966), "The Startling Saga of the Silver Surfer!" by Lee, Kirby, Joe Sinnott (inks) and Sam Rosen (lettering), page 10

Barry Windsor-Smith: I never saw Jimi Hendrix play, I never saw Jack Kirby draw, and these are two great losses — but I would have loved to have been near Jack Kirby physically. Not if he was doing a convention drawing, as in “Oh Jack, do me a drawing!,” but at the real times when he was really creating I’d love to have been present when he invented the Silver Surfer and when he created Galactus. He’s saying, “OK, I’m going to have this big guy who goes around eating planets.”

Gary Groth: Yeah, just watch him compose pages.

Windsor-Smith: Yeah, and feel… I’d literally be a fly on the wall because I know he was supposed to be a very outgoing man, but I doubt very much that when he was on that level of creativity, that people were around him, or could watch him. It had to happen in private. It’s too fucking energetic. It’s too… It’s close to genius is what it is. Inside our field, it’s as close as we’re going to get for a bloody long time it seems. And I would love to have just been able to suck in, feel the energy, the spirit coming out of him. God, talk about being bathed by God’s light or something. This is back to what you were saying about the palpable and the non-palpable when it comes to art — I as a person wouldn’t have been able to understand and translate his power, because it’s entirely his own meta-energy. But it’s like you don’t have to understand what the sun is and how it works in order to get suntanned. I would have liked to have gotten a slight brush, metaphorically, of the heat that must have come out of Jack Kirby when his mind was really, really roaring. And to think he could translate it onto paper, with a stubby bleedin’ pencil to me is just one of the all-time gases of this world. And we are very lucky that we were around and at an impressionable age when that stuff was coming out.

- "The Barry Windsor-Smith Interview" by Gary Groth, The Comics Journal #190 (September 1996)

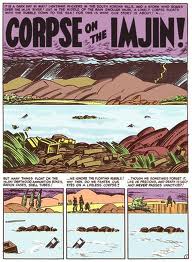

5) Bernard Krigstein EC stories, especially "Master Race" and "The Flying Machine" with Al Feldstein

Bernard Krigstein (1919 - 1990)

Al Feldstein (1925 - 2014)

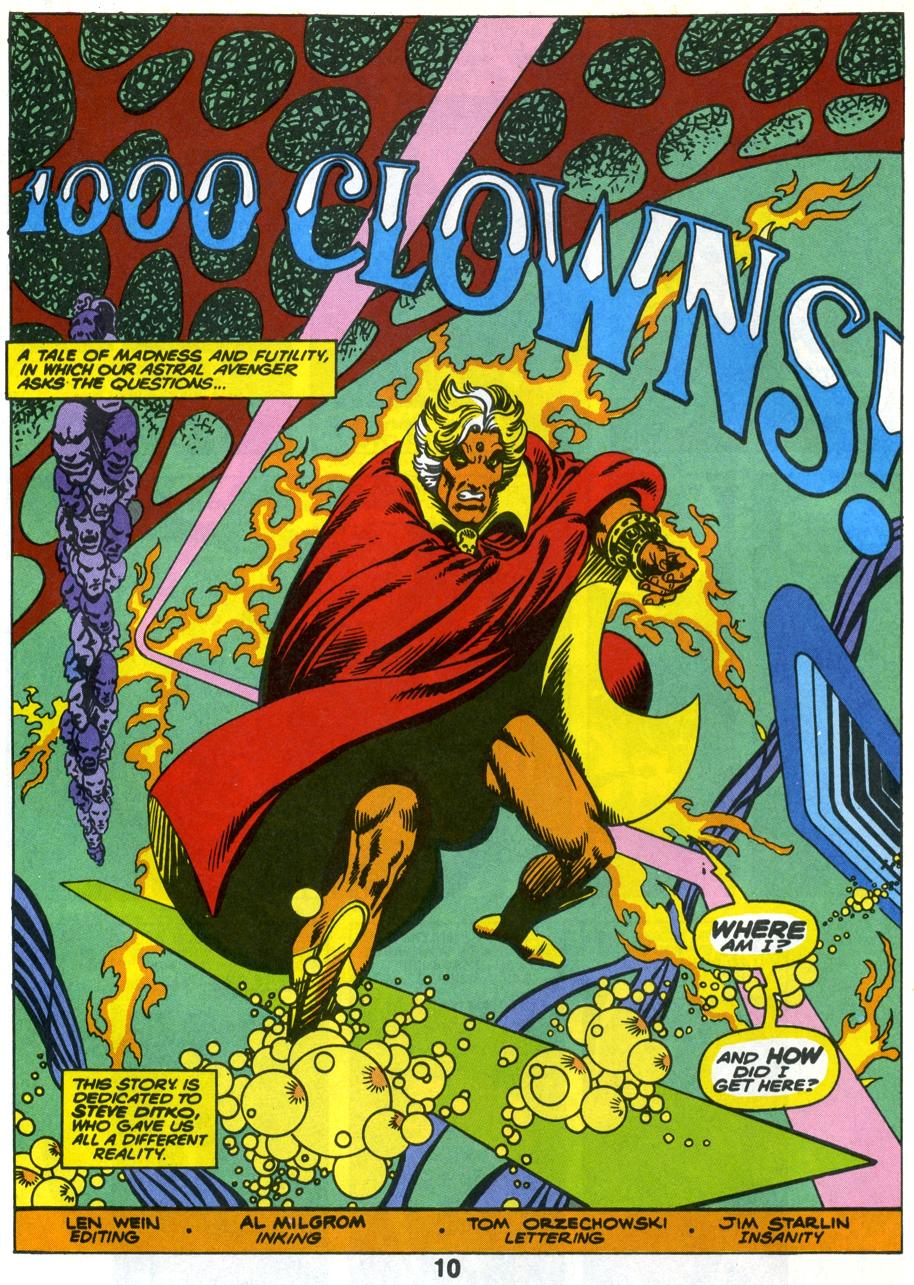

6) Warlock by Jim Starlin

Jim Starlin (1949 to present)

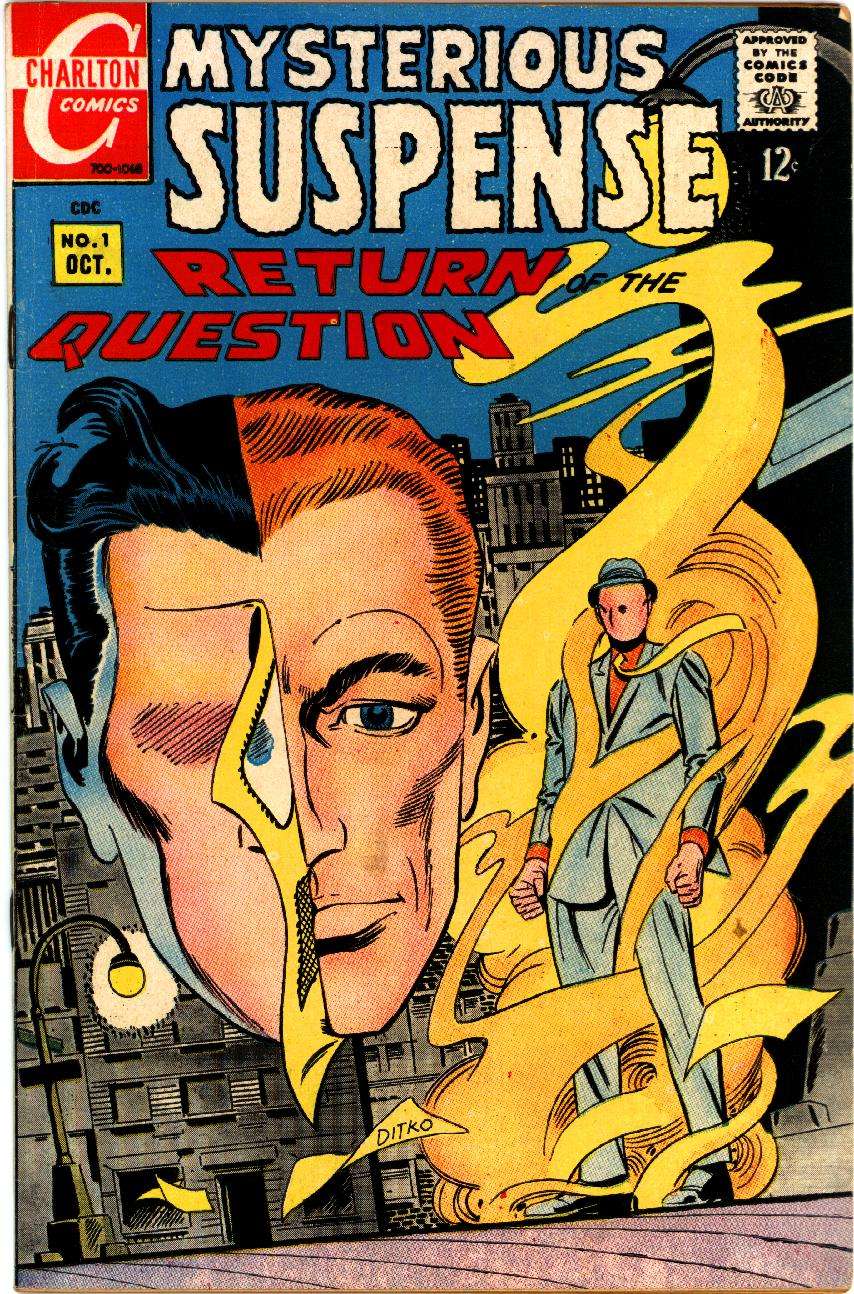

7) Dick Giordano editorship at Charlton (1967 - 1968): Mysterious Suspense #1 by Steve Ditko and "Children of Doom" (Charlton Premiere vol 2, #2) by Dennis O'Neil (as Sergius O'Shaughnessy) and Pat Boyette

Pat Boyette (1923 - 2000)

Steve Ditko (1927 to present)

Dennis O'Neil, early comic book critic Dwight R. Decker, and Dick Giordano (1932 - 2010), late 1960s comic book convention in New York City

Pat Boyette (1923 - 2000)

Steve Ditko (1927 to present)

8) Will Eisner - covers with Lou Fine (1939 - 1941) and The Spirit

Will Eisner (1917 - 2005)

Lou Fine (1914 - 1971)

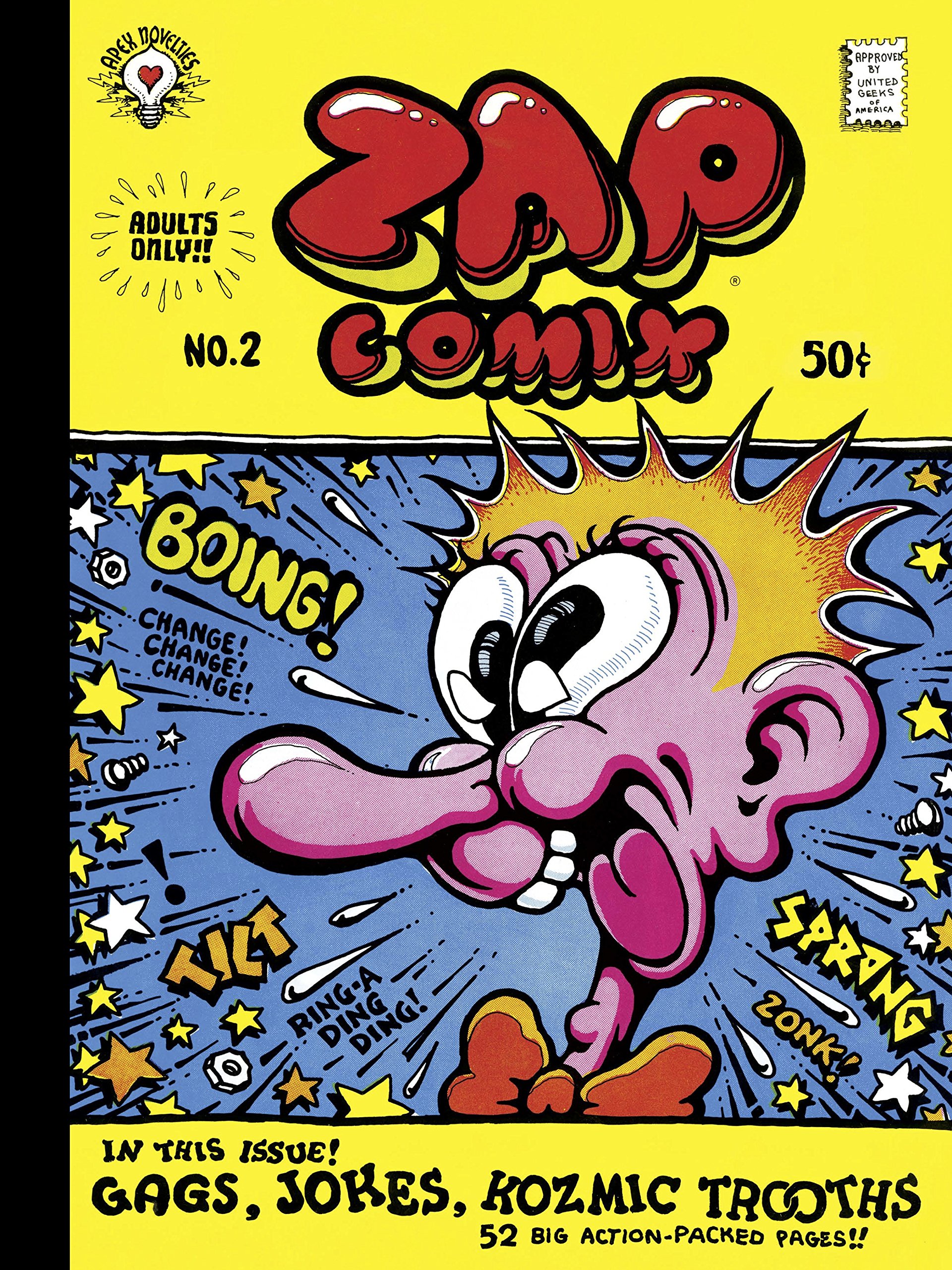

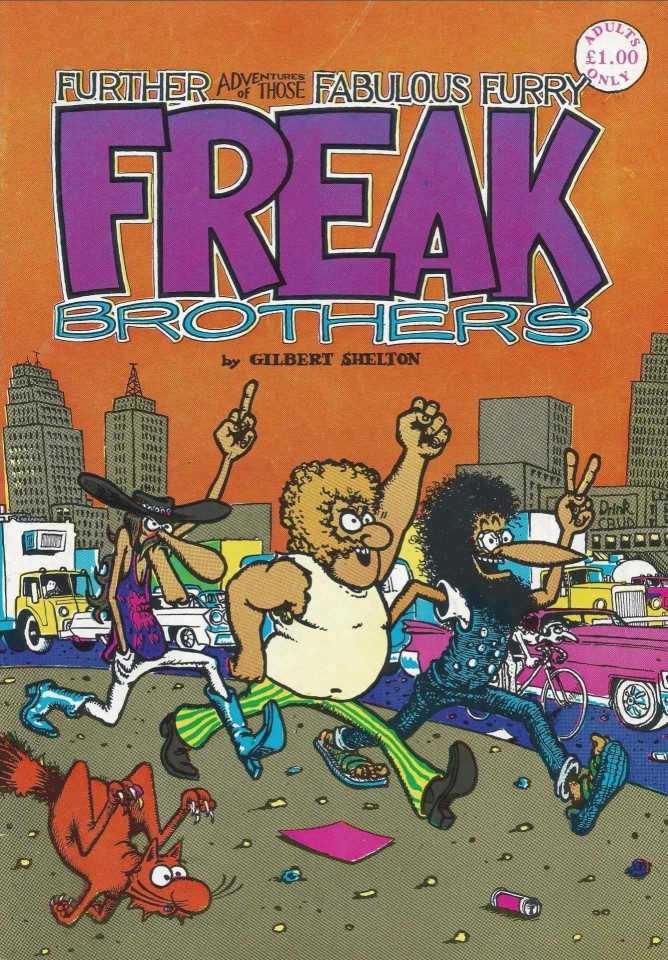

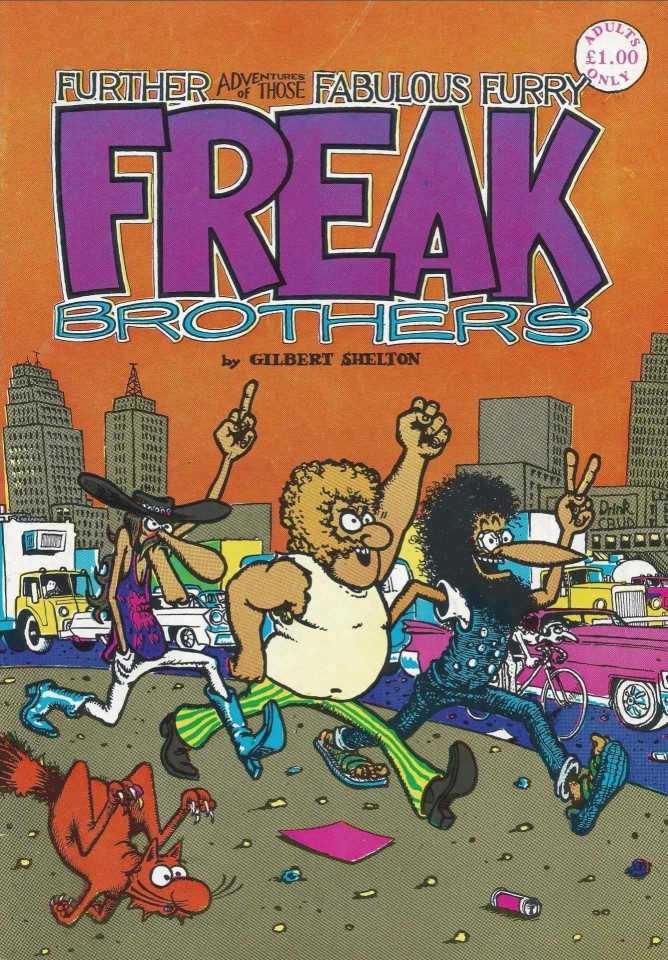

9) Best undergrounds: Zap Comix etc. by Robert Crumb, Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers #1 & 2 by Gilbert Shelton, and Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary by Justin Green

Gilbert Shelton and Robert Crumb, pre-boomers raging against the dying of the light?

Gilbert Shelton and Robert Crumb, pre-boomers raging against the dying of the light?

Justin Green, writer/artist of Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (1972), the most impressive sustained narrative to emerge from the undergrounds. His harrowing account of the ravages of OCD and Catholic guilt and his resultant search for psychological freedom was a huge influence on autobiographical comic stories, particularly Art Spiegleman's Pulitzer Prize and National Book Critic's Circle Award winner, Maus: A Survivor's Tale.

"I know of no other tale in the undergrounds as wildly hilarious as the 18 pager in the back of Freak Brothers #2."

With all due respect to Mr. Green's literary luster and artistically profound catharsis, I know of no other tale in the undergrounds as wildly hilarious as the 18 pager in the back of Freak Brothers #2 in which our hirsute trio gets kicked out of their apartment and then go their separate ways to return home to their parents and families, or the lack thereof in the case of Freewheeling Franklin. No wonder the godfather of the undergrounds Harvey Kurtzman once referred to Shelton as "the pro of the group." Despite the dopiness of the era's topical settings, the humorous ribbing of the squares, hippies, John Birchers, bikers and a Popeye-lookalike pappy remains as pungent as when the comic came out in 1972.

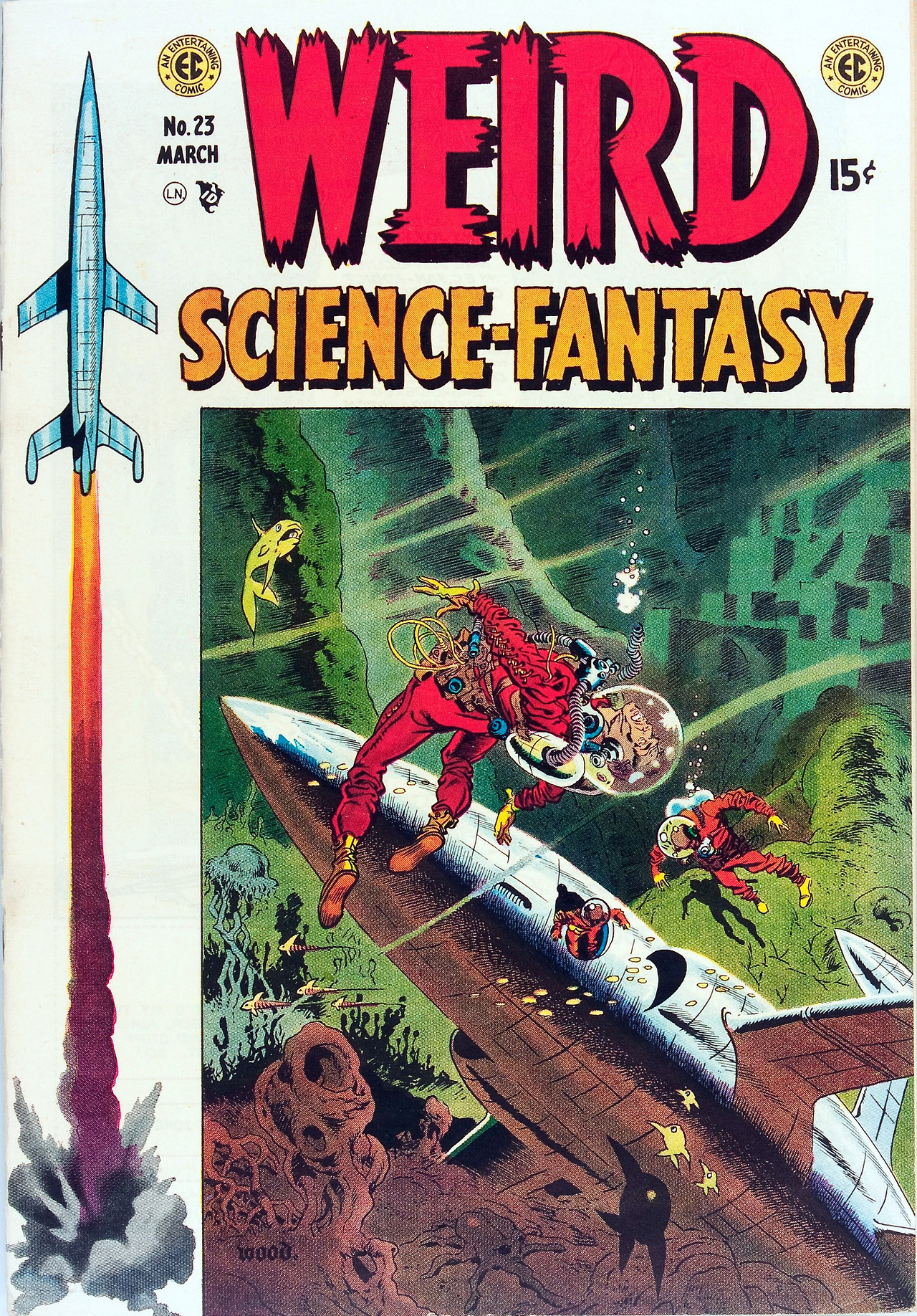

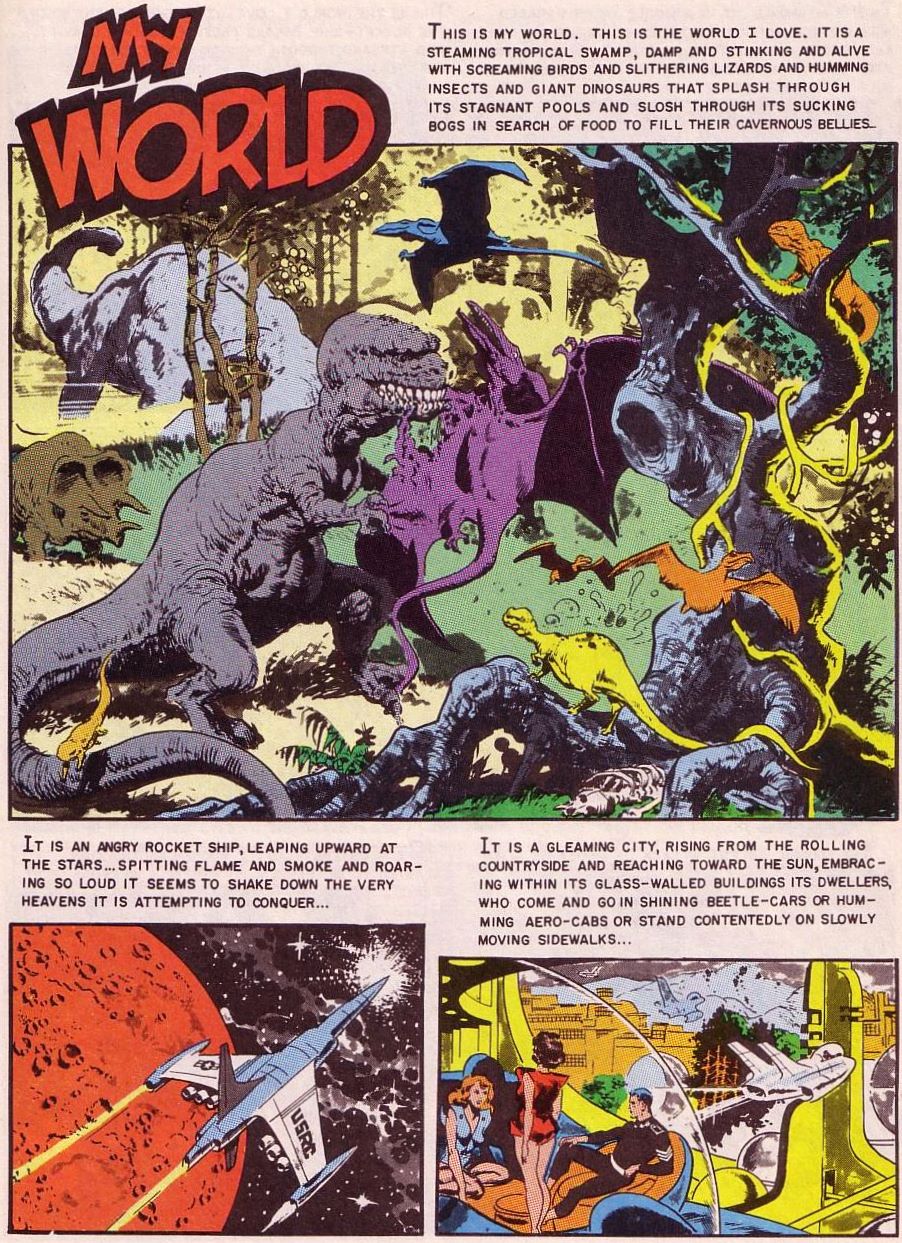

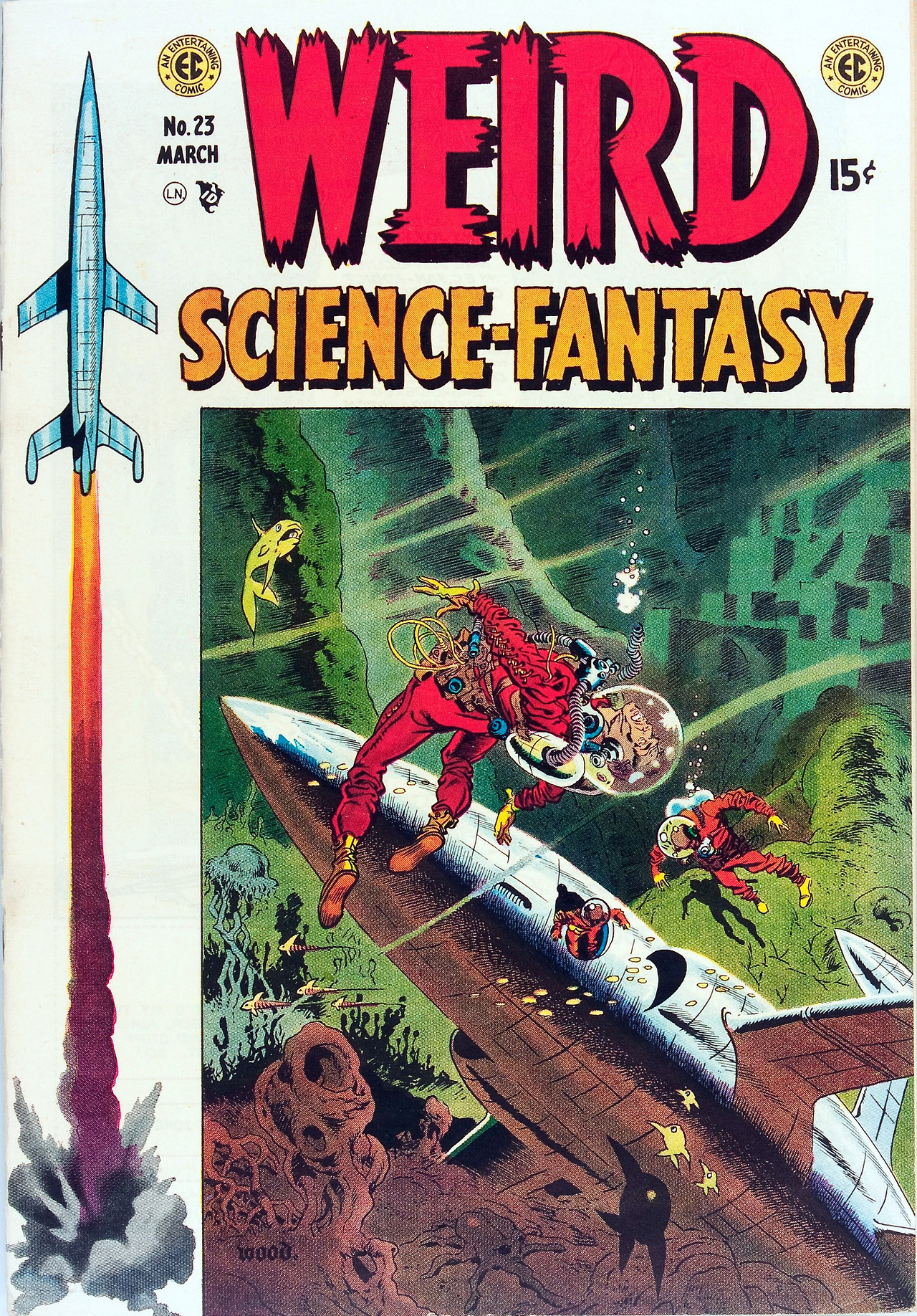

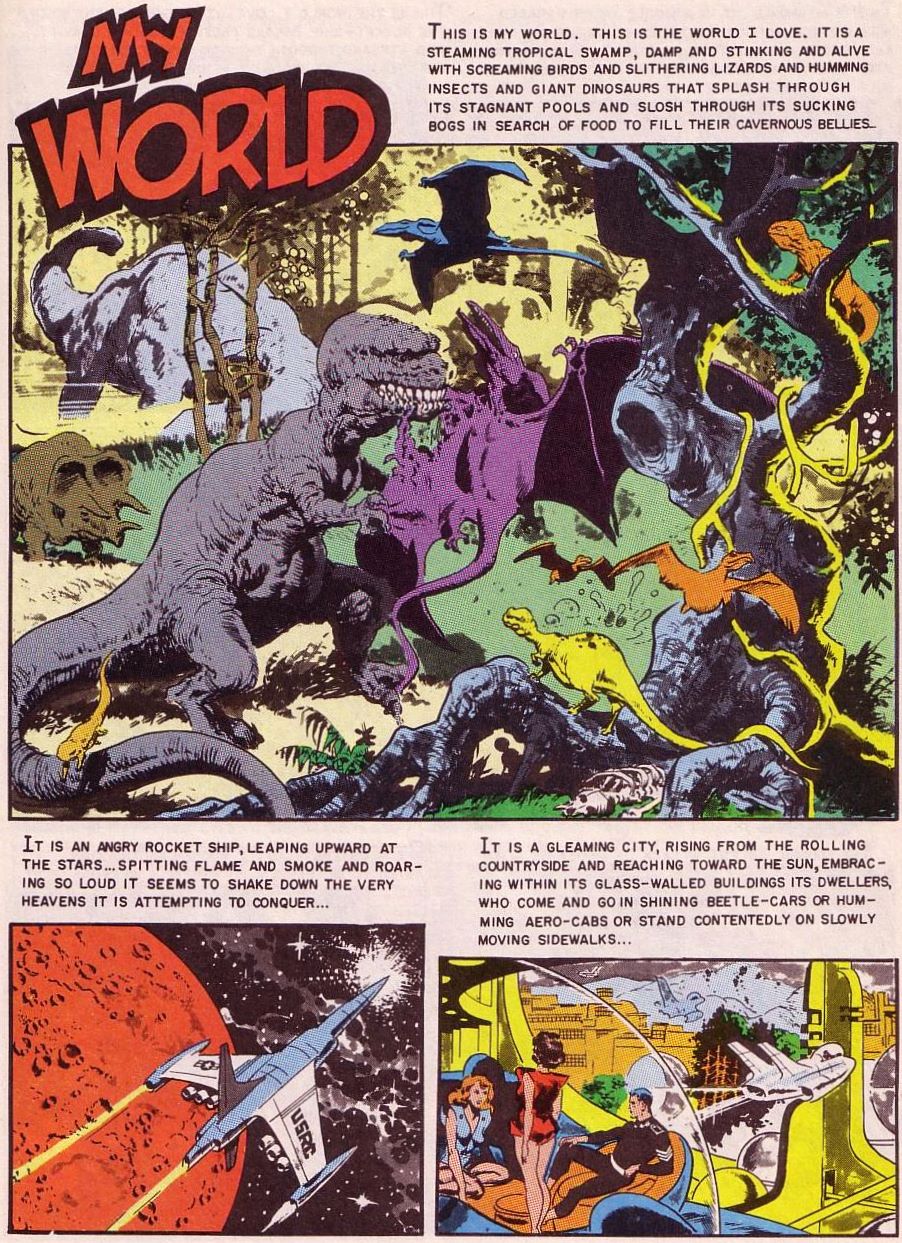

10) EC science fiction stories by Wallace Wood

Wallace Wood (1927 - 1981)

Wallace Wood (1927 - 1981)

* Honorable mention and close calls:

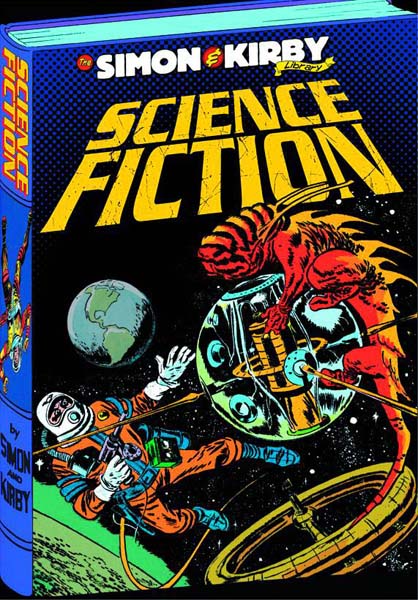

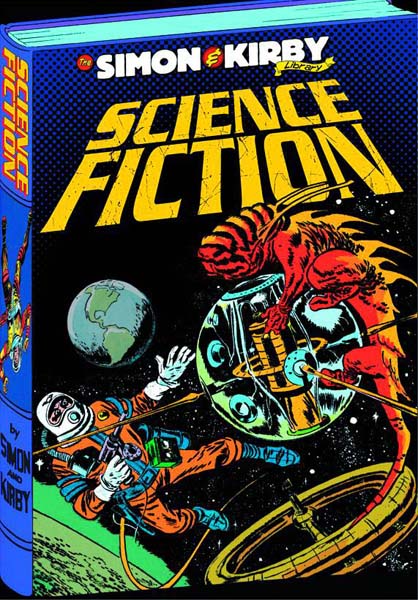

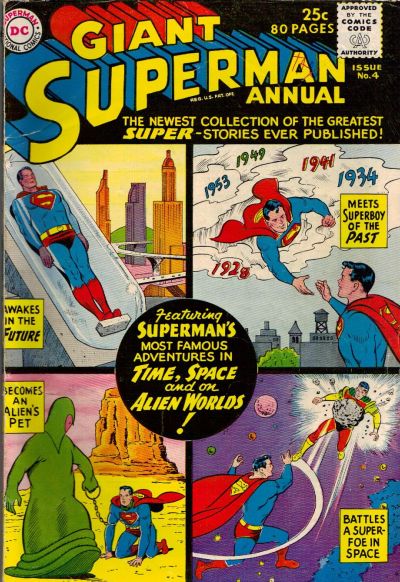

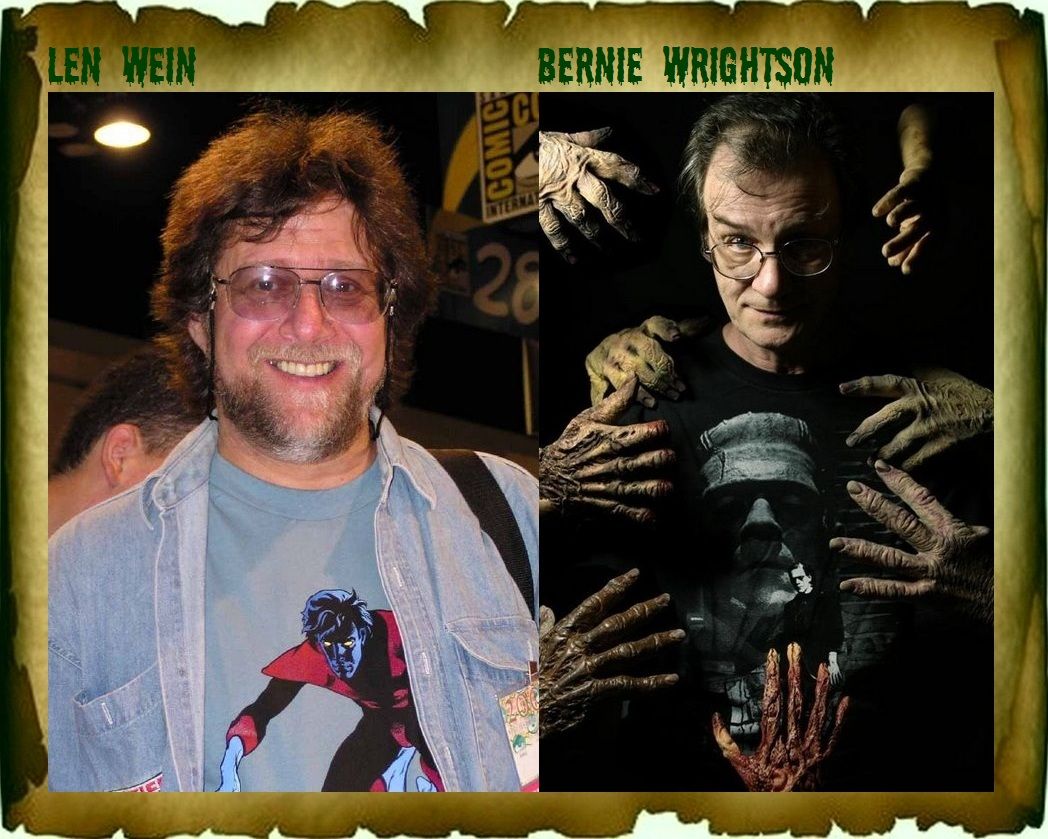

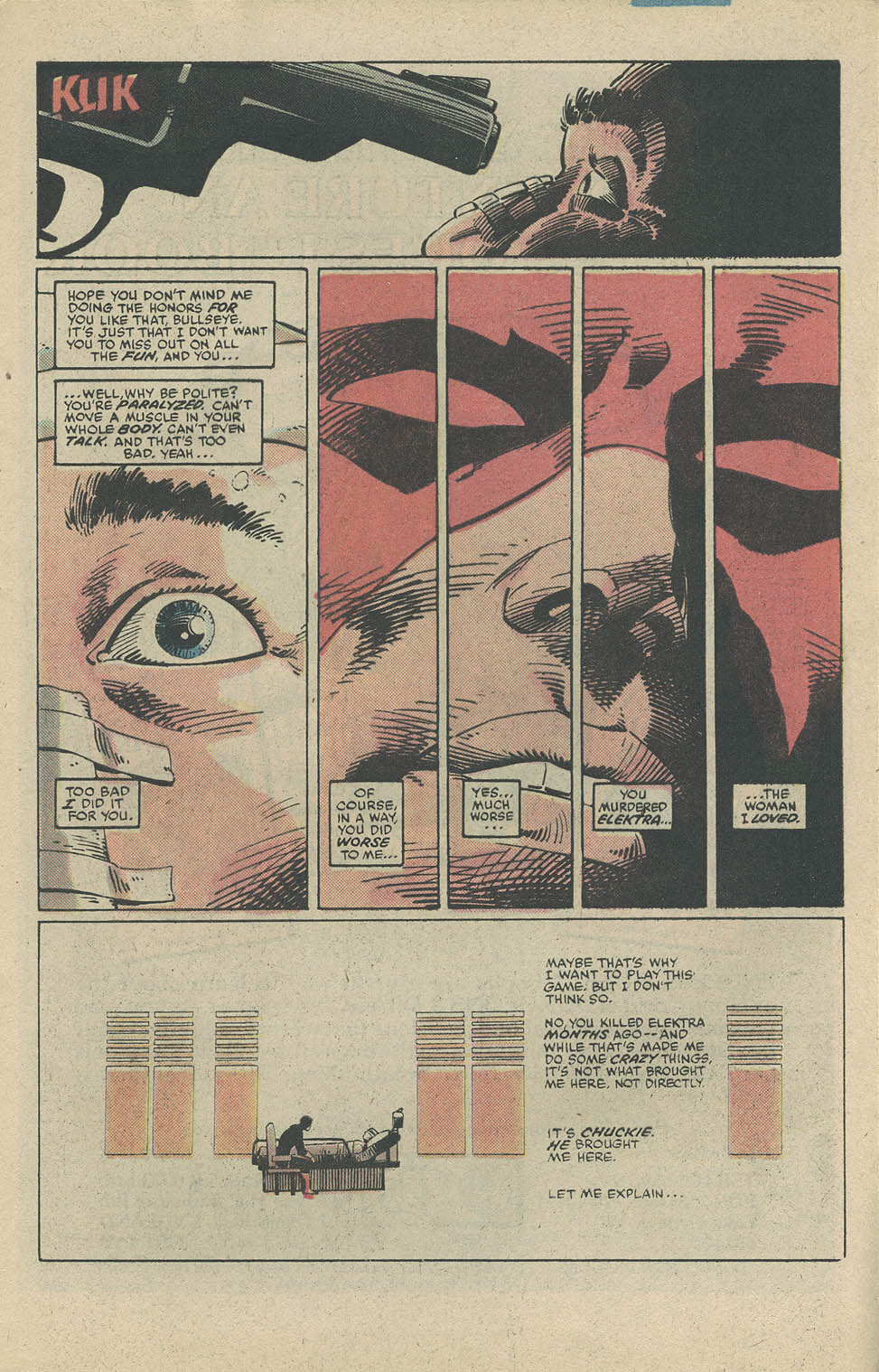

Plastic Man and crime comics by Jack Cole, Famous Funnies and EC sf covers and the story "Squeeze Play" by Frank Frazetta, crime and sf stories by Simon & Kirby, Mort Weisinger-edited Superman titles, Dr. Strange by Lee & Ditko, Nick Fury: Agent of Shield and other Marvel stories by Jim Steranko (especially "At the Stroke of Midnight"), Archie Goodwin's scripts on Blazing Combat, His Name is Savage! with Gil Kane and Manhunter with Walt Simonson, Batman and Detective Comics by Dennis O'Neil and Neal Adams, Phantasmagoria by Kenneth Smith, Conan the Barbarian by Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith, Avengers by Roy Thomas and Neal Adams, Swamp Thing by Len Wein and Bernie Wrightson, American Splendor by Harvey Pekar, 70s & early 80s fanzine art of Dennis Fujitake, Daredevil by Frank Miller and Daredevil Born Again and Batman Year One by Miller and David Mazzucchelli, Sandman by Neil Gaiman et al., Ghost World by Daniel Clowes, Acme Novelty Library by Chris Ware, New X-Men # 121 by Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely

Jack Cole (1914 - 1958)

Frank Frazetta (1928 - 2010) - Looking as lithe and full of dashing, daring-do as one of his sublime renderings.

The dynamo team of Simon and Kirby (S & K) in the early 1950s were matching the EC genre books blow-for-blow.

Jim Steranko (1938 - present)

Archie Goodwin (1937 to 1998)

Walt Simonson (1946 to present)

Gil Kane (1926 to 2000)

Phantasmagoria #4, artwork by Kenneth Smith and Michael Kaluta.

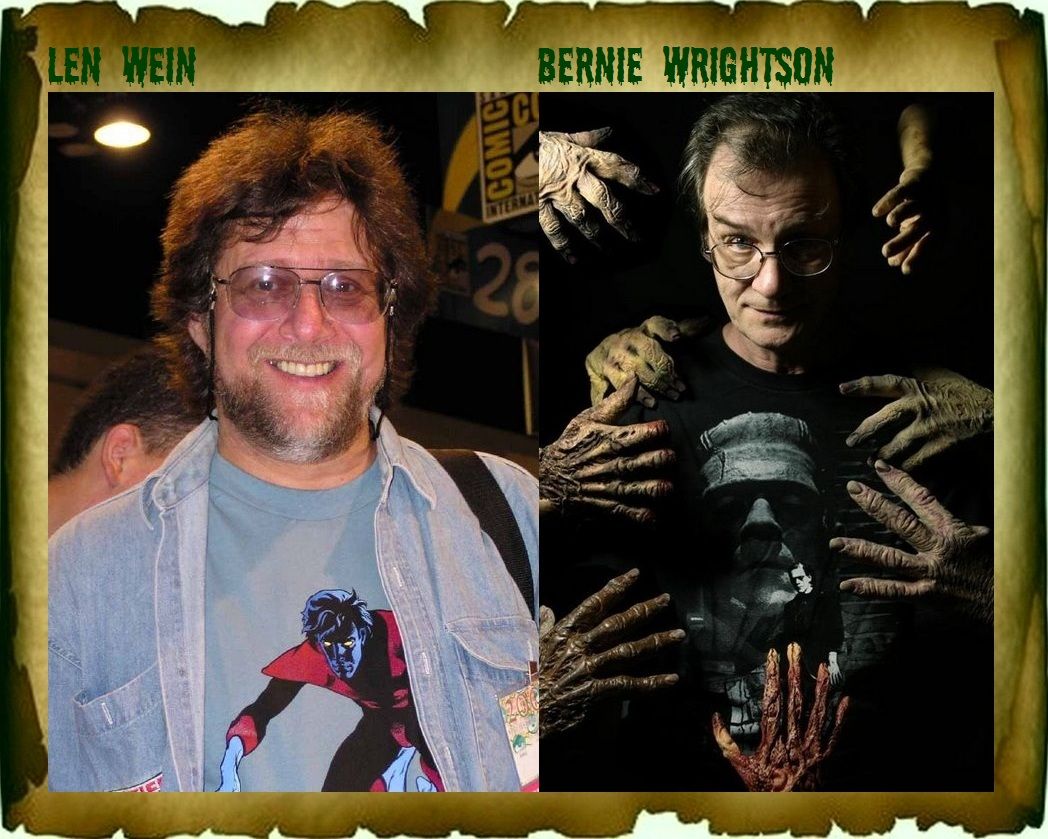

The creators of Swamp Thing: Len Wein (1948 to present) and Bernie Wrightson (1948 to 2017)

Harvey Pekar (1939 - 2010)

Frank Miller (1957 to present)

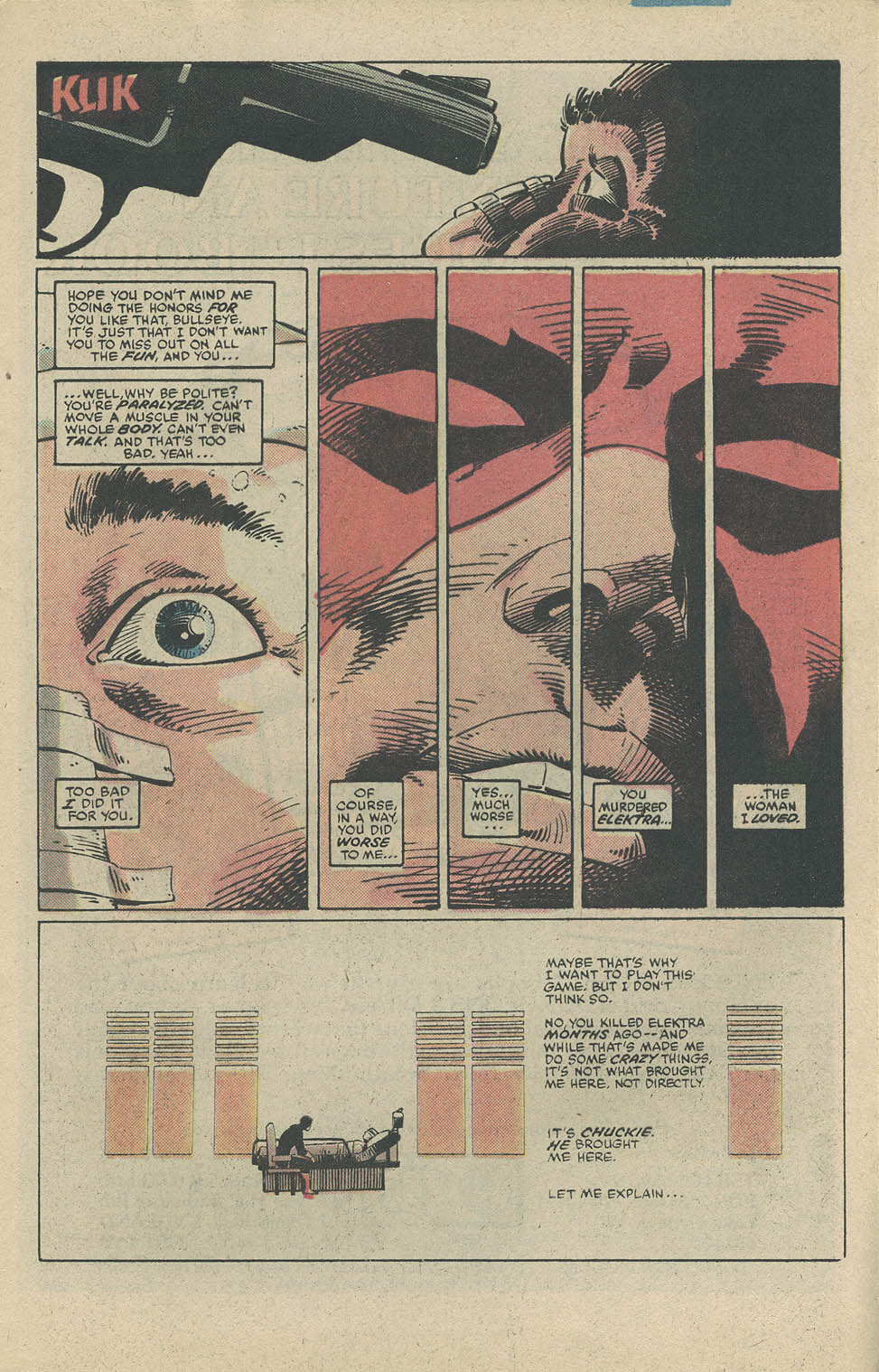

Daredevil #191 (February 1983), "Roulette." Story & art by Frank Miller, inks by Terry Austin.

David Mazzucchelli (1960 - present)

Chris Ware (1967 to present)

Frank Quitely (1968 to present) and Grant Morrison (1960 to present)

New X-Men #121 (February 2002)

Jack Cole (1914 - 1958)

Frank Frazetta (1928 - 2010) - Looking as lithe and full of dashing, daring-do as one of his sublime renderings.

The dynamo team of Simon and Kirby (S & K) in the early 1950s were matching the EC genre books blow-for-blow.

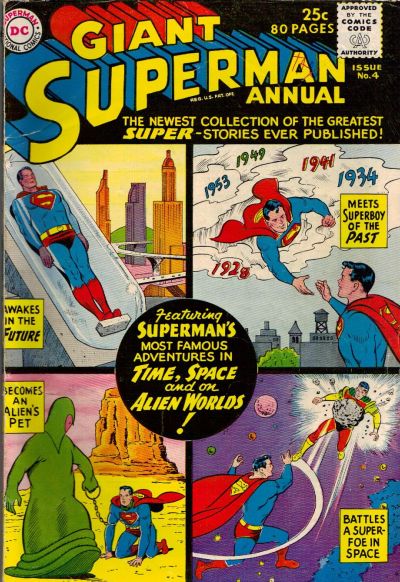

Mort Weisinger (1915 - 1978) helped to found, with Julius Schwartz and Forrest J. Ackerman, the first science fiction fanzine, The Time Traveler (1932) which led to organized fandom and networking, and later laid the groundwork for comics fandom. [And where would comic books be without the resultant San Diego ComicCon, you know, where these lonely little genre storytelling booklets are now drowned out and marginalized by all this new post-literate slick digital crap, anime, cosplay, two bit actors, etc. amid throngs of hundreds of thousands? - ed.] With Schwartz he became a prominent literary agent, helping to put H.P. Lovecraft and Ray Bradbury on the map and he also helped to promote the career of actor George Reeves, star of the Adventures of Superman tv show. Weisinger's time as editor of Superman from 1941 to the 1960s was marked by charming, wholesome stories and remarkable improvements with such whiz-bang concepts as Kryptonite, Supergirl, Krypto the Superdog, the Bottled City of Kandor, the Phantom Zone, the Bizarro world and the Legion of Superheroes. But Weisinger also was a major league asshole, bullying micromanager and verbal abuser extraordinaire who browbeat and terrorized generations of writers and artists, scaring away Stan Lee's eventual able understudy Roy Thomas circa 1965 and instilling into young superhero prodigy Jim Shooter not only the rudiments of adventure storytelling but also mentally roughing up Shooter considerably in the process. (Shooter was later the notoriously maligned and still controversial Marvel editor in chief, see R.S. Martin's persuasive apologia on Shooter's behalf .)

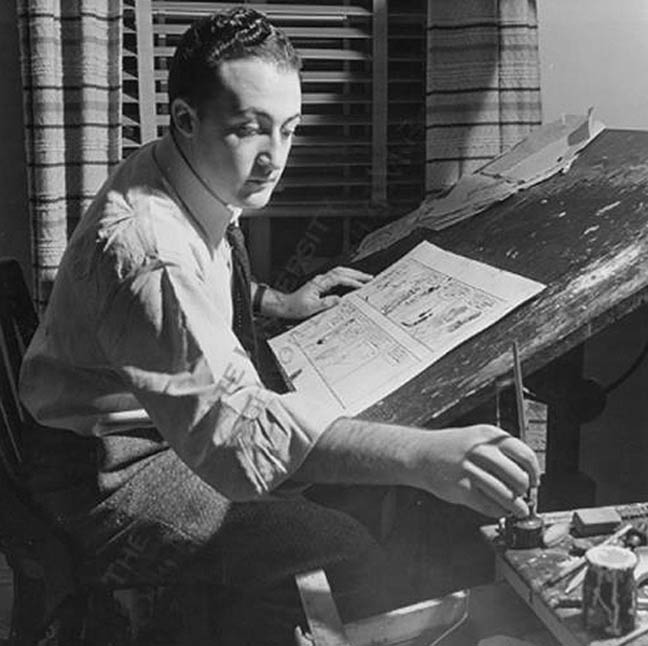

Lee and Ditko in their prime, January 1965.

Jim Steranko (1938 - present)

Archie Goodwin (1937 to 1998)

Walt Simonson (1946 to present)

Manhunter by Goodwin and Simonson, a back-up feature in Detective Comics #437 - 443, July 1973 to July 1974. Frank Miller's startlingly ultra-violent, relentlessly forward-rushing Ronin, published about ten years later, didn't just emerge from the ethers.

Gil Kane (1926 to 2000)

Kenneth Smith (1943 - present) - Freelance fantasy artist, renegade author, critic and retired college professor known to many comic fans for his abrasive, intellectually supercilious, mercilessly opaque, and hyper-complex philosophy columns, highfalutin diatribes and occasional paens of praise to the worthy in the adversarial trade publication The Comics Journal. Dr. Smith (who holds a PhD. in philosophy from Yale University, where he thrived on the most difficult of material such as Kant, Hegel, and Nietzsche) was also an early EC fan from East Texas, a contributor to the top quality EC fanzines Spa Fon and Squa Tront, and an artistic protege of Frank Frazetta and Wallace Wood. While attending graduate school at Yale, Smith was granted the opportunity, at Phil Seuling's pioneering NYC conventions in the late 60s, to meet and get direct tutelage from these artistic role models whom he correctly called "great talents." His lavishly produced self-published series Phantasmagoria (1970 - 1977), produced as a midnight oil labor of love when he got home from his teaching gig at Louisiana State University and attended to his family duties as a married man with a large family, was not really a comic book most of the time, but a series of astoundingly well-illustrated allegorical picto-philosophy fables featuring poetic ruminations about civilization-influenced modes of thought (which seem so absolute to the "obtuse" as Smith loves to say but are really relative to the parameters of what's see-able and think-able within the confines of a given historical epoch) and the predicaments of human existence which used stories about reptiles, fish, ants and other fantasy elements as his vehicles. It was an esoteric treat for the few connoisseurial collectors who doted on it, which gained wide respect from his peers and also was of some influence on the field of animation. Of special note to fans of his mesmerizing Creepy and Eerie cover paintings would be the proper comic stories -- defined as such by their use of word balloons, captions and sequential narrative panels -- "Sinking Feeling" and "Parasite." Both of these compelling sf tales were self-published by Smith in Phantasmagoria #2 (Spring 1972) after getting rejected by publisher Jim Warren despite their thought-provoking stories and luscious, subtly tinted and exquisitely modeled artwork. Another visual tour de force (despite the cold, cerebral and often dissociated quality conveyed by Smith's masterful pencils) was issue #4 (Summer 1974), which featured delectable collaborations with Michael Kaluta, pulp and sf great Hannes Bok, Frank Frazetta, Frazetta's personal art tutor Roy G. Krenkel, and Wallace Wood.

Phantasmagoria #4, artwork by Kenneth Smith and Michael Kaluta.

Avengers #95 (January 1972) by Roy Thomas, Neal Adams and inks by Tom Palmer (among the richest and most sumptuous in all of comicdom).

Tom Palmer (1942 to present)

The creators of Swamp Thing: Len Wein (1948 to present) and Bernie Wrightson (1948 to 2017)

Harvey Pekar (1939 - 2010)

Frank Miller (1957 to present)

Daredevil #191 (February 1983), "Roulette." Story & art by Frank Miller, inks by Terry Austin.

David Mazzucchelli (1960 - present)

Chris Ware (1967 to present)

Frank Quitely (1968 to present) and Grant Morrison (1960 to present)

New X-Men #121 (February 2002)